Written by Juliette Burns, Class of 2026

There has been so many amazing Native students over the years – just incredible. I think Willamette has been incredibly blessed with having Native students come here who impacted the education of all students at Willamette and certainly were hugely supportive of one another, helped each other get over the finish line.

- Rebecca Dobkins, former Native and Indigenous Student Union faculty advisor, November 2023.1

Throughout Willamette University’s history, the school has been undeniably tied to the Indigenous populations in the Willamette Valley region. The very begining of the university was as the Oregon Indian Mission Manual Labor School, started by the Methodist missionary Jason Lee in the 1830s.2 Indigenous children at the school were taught manual farming skills, being made to work the land of the settlers. By 1844, the Manual Labor School had failed, and was substituted with the Oregon Institute, a school for the children of white settlers. In 1853, the school was chartered by the Oregon territorial legislature as Willamette University.3 It was during this decade that Indigenous tribes were removed from their land and gathered onto reservations. Most Indigenous people in the region were brought to the Grand Ronde reservation, which today is located around 40 minutes outside of Salem.

The Indigenous student population at Willamette University, which can be traced back to the early 1900s, has always been low.4 It was a larger than typical group of incoming Indigenous students which brought about the beginnings of the Native and Indigenous Student Union (NISU), a student organization which would bring important change to the campus.

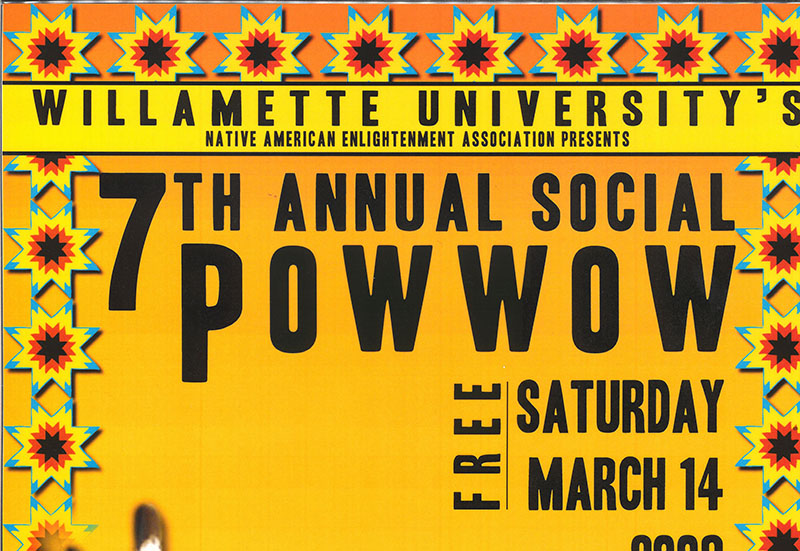

Willamette’s incoming class of 2001 included fourteen Indigenous students, the largest amount in one class that former NISU advisor Rebecca Dobkins can recall.5 In late 2001, several of these students came together to create a space on campus where fellow Indigenous students could find community and solidarity, and could organize events and projects to bring awareness of contemporary Indigenous culture and presence to the campus. The Native American Enlightenment Association, as it was then called, held its first meeting in September of that year. This name was chosen by Neeka Somday, the first (co)president of the club and one of the founding members. The motivation behind the name was the desire to bring ‘enlightenment’ to the campus regarding contemporary Indigenous culture. This name remained for nearly a decade and a half. It was changed in 2014 to the Native and Indigenous Student Union.6 During their first couple of years, club membership was low, yet they still planned a variety of events for themselves and the wider campus.7 From the beginning, the group had clear ideas of what they wanted to work towards, and they would go on to accomplish them.

The NISU had two main goals. First, they wanted to bring awareness of Indigenous culture through campus events and activities and off-campus trips to Pow Wows, lectures, and other events put on by universities and Indigenous groups. Second, they wanted to forge relationships with off-campus Indigenous groups and individuals.8

NISU was involved in assisting with and planning many events. Sometimes these would be advertised for the whole campus to participate, and sometimes they would be more private affairs—get-togethers for Indigenous students. Outside of larger campus-wide events, the NISU would travel to wintertime pow wows, visit museums, and get together for dinners and potlucks. They also had their weekly meetings, where students could relax, plan events, and discuss current affairs.9

From the very start of the organization, one of their main goals had been to plan a Pow Wow for the campus. Pow Wows are Indigenous community gatherings with dancing, vendors, and socializing for Indigenous peoples from around the region. A current member of the NISU—Hattie Mercier—poignantly describes their importance: “I see Pow Wows as a way to preserve our culture and celebrating heritage through regalia, I see it as a way to strengthen community, and to tell our story. That against all odds, by losing everything, we still persevered and we’re still here. And that we’re here to stay.”10 This celebration and awareness was at the core of the club’s efforts to begin a tradition of Pow Wows on campus.

In March 2003, the NISU brought the First Annual Social Pow Wow to Willamette University. This event took months of work from the club, the faculty who worked with them, and volunteers. The Pow Wow involved various dance groups who introduced participants to intertribal dances. Vendors sold fry bread, crafts such as beadwork, jewelry, and clothing, and Indigenous music, and a raffle was set up to give away a Pendleton blanket.11 The club had to arrange matters with the dance groups, get contracts for the vendors, and find prizes for the raffle, among many other tasks. The work paid off—the Pow Wow was a smash hit among the students and visitors.

The event was considered a great success by the organizers, with hundreds in attendance coming from both on and off campus. Every March for almost two decades, the Annual Social Pow Wow at Willamette University brought hundreds of visitors to the campus, including groups such as students from Chemawa Indian School. Rebecca Dobkins—a professor specializing in Indigenous studies and the club advisor for many years—said regarding the Pow Wows: “Putting on an event like that created a sense of belonging, not just for the student group but for the native community in our area.”12

The Chemawa Indian School is one of very few remaining off reservation Indigenous boarding schools in the country, standing just outside of Salem. During the first few years of the NISU’s existence, members of the club began an informal tutoring program, where they would travel to the school and talk with the students about college, the SATs, and other academic concerns. This relationship had been an expressed goal of the club from the start.13 The faculty at the Chemawa school noticed this initiative, and in the Spring of 2005, Larry Myers, the Chemawa superintendent, approached Willamette President Lee M. Pelton with a desire to make this an official program between the schools. By the fall of the same year, there was a class made available to Willamette students to tutor at the Chemawa Indian School for class credit. A graduated founding member of the NISU helped run the program, continuing the work they began as a college student creating and aiding Indigenous endeavors.

The Willamette University land acknowledgement was finalized by the university in 2019, after students pushed for an acknowledgement from the school of the land’s connection to the Indigenous Kalapuya people. The NISU president at the time, Adriana Nicolay, was on a subcommittee of the university’s Council on Diversity and Social Justice, which drafted the acknowledgement.14 The land acknowledgement—though so often just words and not actions—brings an awareness to the university’s origins and the past and continued presence of Indigenous people in the area, a core goal of the NISU.

The links that the Native and Indigenous Student Union had with various Indigenous people and groups throughout the region grew from a web of connections held by faculty members, community members on the university’s Native American Advisory Council, and other Indigenous student groups at universities throughout Oregon. These connections helped the club to bring in various Indigenous performers—from dancers to storytellers—and forge long term relationships, such as with Bob Tom, the longtime Master of Ceremonies at the Annual Pow Wow and an elder in the Grand Ronde.15 The NISU also provided a site for community gathering, as their Annual Pow Wows were an important event for many.

Throughout the years, a core challenge for the NISU, Indigenous students, and the faculty who worked with them has been a lack of formal, administrative support. Many of the events and programs aimed at Indigenous students hinged on the continued work of faculty members such as Gordy Toyama—the former Director of Multicultural Affairs and a large supporter of the students—and Rebecca Dobkins.16 Without institutional support, the faculty supporting the students took on larger workloads, and the students themselves became important advocates and planners for action and change on and off campus. The Chemawa Partnership Program began entirely due to Indigenous student action, and the Willamette University Land Acknowledgement was also an Indigenous student-led initiative.

The NISU and Indigenous students as a collective have seen these challenges and brought about large scale change, creating new protocol and programs. However, regardless of their perseverance and ability, the students of the NISU should not have been asked to make these changes themselves. The need for institutional support for Indigenous students is still an issue on campus.

Following the retirement of faculty and staff members such as Gordy Toyama and Rebecca Dobkins, the onset of COVID-19, and the subsequent lack of Indigenous focus and leadership among the faculty; many of the programs and events centered around Indigenous people have been put on pause. As of 2023, The last Pow Wow on campus took place in March 2019. The 18th Annual Social Pow Wow was scheduled to occur on March 14th, 2020, but was canceled. The Chemawa Partnership Program is no longer being offered as a course, and the Native American Advisory Council has been dissolved. Despite these new challenges, the Native and Indigenous Student Union continues to be a space on campus where Indigenous students can find community amongst each other. They hold weekly meetings and run events for Native American Heritage Month in November. In November 2023, they hosted a storytelling night and a beading workshop, and faculty member David Craig gave a campus history tour and hosted Indigenous author David G. Lewis on campus.17

The NISU is here today because of the hard work and perseverance of Indigenous students. Throughout the years, they have held fast to the goal of showing the campus and the world that Indigenous cultures are still here. They have worked within the Indigenous community in Salem and the Willamette Valley area, maintaining relationships and using their status as college students to help others, such as the Chemawa students. The NISU has also worked with non-Indigenous people, teaching them various aspects of Indigenous cultures through dance, film, storytelling, and crafting. The club is uncertain of its future with the loss of many Indigenous programs and supportive staff—but regardless, Indigenous students will always be a presence on campus.

That against all odds, by losing everything, we still persevered and we’re still here. And

that we’re here to stay.

- Hattie Mercier, Willamette University Class of 2027, November, 2023.18

Endnotes

Click to expand

- ˆ Rebecca Dobkins, Dobkins – NISU Interview, conducted by Juliette Burns, 14 November 2023.

- ˆ Cary Collins, “Indian Boarding Schools,” last modified July 29, 2022, https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/indian_boarding_school/

- ˆ Collins, “Indian Boarding Schools.”

- ˆ Willamette University, “Banquet in Portland,” Willamette Collegian (Salem, OR), January 20, 1910

- ˆ Dobkins, Dobkins – NISU Interview.

- ˆ Dobkins, Dobkins – NISU Interview.

- ˆ Box 26, Folder 47, Native and Indigenous Student Union (NISU) (Native American Enlightenment Association (NAEA)), 2001-2018, Native and Indigenous Student Union (NISU) (Native American Enlightenment Association (NAEA)), Willamette University Office of Student Activities Records, Willamette University Archives, https://willamette.libraryhost.com/repositories/2/archival_objects/87327

- ˆ Ben Nystrom, “Native American student club formed at WU,” Willamette Collegian (Salem, OR), 1 November, 2001

- ˆ Gordon Toyama, Toyama – NISU Interview, conducted by Juliette Burns, 8 December, 2023.

- ˆ Hattie Mercier, Personal Communication with author, 28 November, 2023.

- ˆ Stephanie Soares, “Powwow brings Native American cultural ceremonies to Willamette,” Willamette Collegian (Salem, OR), March 19, 2003

- ˆ Dobkins, Dobkins – NISU Interview.

- ˆ Nystrom, “Native American student club formed at WU.”

- ˆ Colleen Kawahara, Email communication to author, 5 December, 2023.

- ˆ Soares, Stephanie, “Powwow brings Native American cultural ceremonies to Willamette;” Avi Katz, “Native American storyteller tells tales,” Willamette Collegian (Salem, OR). 30 April, 2003; Chelsea Wright, “Bringing a tradition to life,” Willamette Collegian (Salem, OR). 31 October, 2002

- ˆ Dobkins, Dobkins – NISU Interview.

- ˆ Juliane Corpus, “November is Indigenous Peoples Heritage Month,” 30 October, 2023; Willamette University, “Tribal Histories of the Willamette Valley by David G. Lewis,” 20 November, 2023.

- ˆ Hattie Mercier, Personal Communication with author, 28 November, 2023.

Works Referenced

Click to expand

- Box 26, Folder 47. Native and Indigenous Student Union (NISU) (Native American Enlightenment Association (NAEA)), 2001-2018. Native and Indigenous Student Union (NISU) (Native American Enlightenment Association (NAEA)). Willamette University Office of Student Activities Records. Willamette University Archives. https://willamette.libraryhost.com/repositories/2/archival_objects/87327

- Collins, Cary. “Indian Boarding Schools.” last modified July 29, 2022. https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/indian_boarding_sch

- Colleen Kawahara. Email communication to author. 5 December, 2023.

- Corpus, Juliane. “November is Indigenous Peoples Heritage Month.” 30 October, 2023. https://willamette.edu/news/today/past-issues/2023/10/30/november-is-indigenous-peoples-heritage-month.html#:~:text=We%20invite%20you%20to%20learn,and%20participate%20in%20our%20programs.

- Dobkins, Rebecca. Dobkins – NISU Interview. Conducted by Juliette Burns. 14 November 2023.

- Katz, Avi. “Native American storyteller tells tales.” Willamette Collegian (Salem, OR). 30 April, 2003. https://hdl.handle.net/10177/9801

- Nystrom, Ben. “Native American student club formed at WU.” 1 November, 2001. Willamette Collegian (Salem, OR). https://hdl.handle.net/10177/7472

- Mercier, Hattie. Personal Communication with author. 28 November, 2023.

- Soares, Stephanie, “Powwow brings Native American cultural ceremonies to Willamette.” Willamette Collegian (Salem, OR), March 19, 2003. https://hdl.handle.net/10177/9058

- Toyama, Gordon. Toyama – NISU Interview. Conducted by Juliette Burns. 8 December, 2023.

- Willamette University. “Tribal Histories of the Willamette Valley by David G. Lewis.” 20 November, 2023. https://events.willamette.edu/e/5283

- Willamette University, “Banquet in Portland.” Willamette Collegian (Salem, OR), January 20, 1910. https://hdl.handle.net/10177/8611

- Wright, Chelsea. “Bringing a tradition to life.” Willamette Collegian (Salem, OR). 31 October, 2002. https://hdl.handle.net/10177/8539

Image Citations

Click to expand

- Soares, Stephanie, “Powwow brings Native American cultural ceremonies to Willamette.” Willamette Collegian (Salem, OR), March 19, 2003.

- Poster, Powwow, 2009. Box 54, Folder 6. Willamette University Office of Student Activities records, WUA054. Willamette University Archives and Special Collections.

- Poster, Powwow, 2016. Box 54, Folder 6. Willamette University Office of Student Activities records, WUA054. Willamette University Archives and Special Collections.